Tackling Rice Stubble Burning in India: A Policy Proposal Inspired by the US Cap-and-Trade System

Introducing “The Problem of Social Cost”

The issue of rice stubble burning can be framed in the context of Ronald Coase’s essay “The Problem of Social Cost.” Coase argued that when property rights are clearly defined, and transaction costs are low, parties can negotiate to resolve externalities. In this case, farmers burn stubble to save time and reduce costs, but this action imposes a significant social cost on the public through air pollution. If property rights over clean air were well-defined and the negotiation costs were low, affected parties (e.g., residents suffering from pollution) could pay farmers to adopt cleaner methods or invest in alternative technologies, thus internalizing the externality and reducing pollution.

In simpler terms, Coase’s argument means that if everyone knows who owns what and it’s cheap to make deals, people can work out problems like pollution on their own. For example, if people suffering from pollution could quickly pay farmers to stop burning stubble, both sides would find a solution that works for them without strict government rules.

The Problem: Stubble Burning and Its Impacts

Rice stubble burning is a significant environmental issue in India, particularly in the northern states of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. Farmers burn rice stubble primarily due to time constraints between rice harvesting and wheat sowing and manual stubble removal’s labor-intensive and costly nature. While reasonable for farmers, this practice has severe environmental consequences. It contributes significantly to air pollution, leading to respiratory problems, reduced visibility, and long-term health issues for the general public.

Stubble burning releases many toxic pollutants into the atmosphere, including carbon monoxide, methane, volatile organic compounds, and particulate matter, exacerbating air pollution and climate change. Despite the known negative impacts, farmers continue to burn stubble due to the lack of viable alternatives and economic incentives.

Learning from the U.S. Cap-and-Trade System

The U.S. successfully tackled acid rain by introducing a cap-and-trade system for sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions. This system set a firm cap on total emissions and allowed industries to buy and sell emission allowances, creating a financial incentive to reduce pollution. The program led to a significant reduction in SO2 emissions at a lower cost than traditional regulatory approaches.

Adapting Cap-and-Trade for Stubble Burning

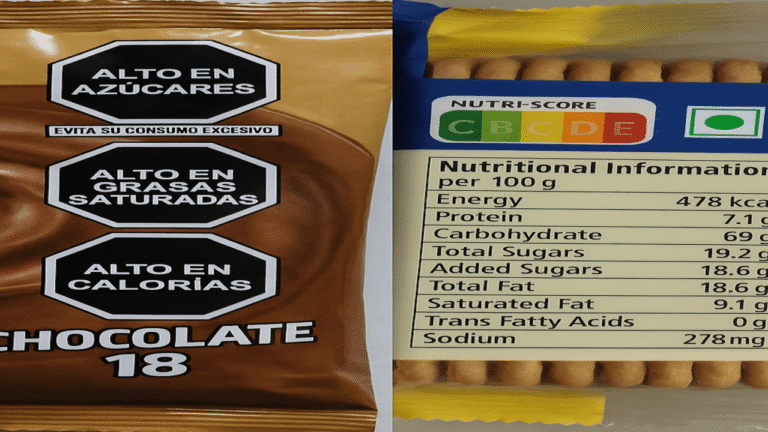

A similar cap-and-trade system can be designed to address the issue of rice stubble burning in India. The policy would involve setting a cap on the total amount of stubble that can be burned and distributing allowances to farmers. Farmers who adopt alternative methods to manage stubble, such as using Happy Seeders or bio-decomposers, could sell unused allowances to those who find it challenging to avoid burning. This would create a financial incentive for farmers to adopt environmentally friendly practices.

Critical Components of the Policy

1. Setting the Cap: The government would cap the amount of stubble burning allowed each season. This cap would gradually decrease to encourage continuous improvement in stubble management practices.

2. Issuing Allowances: Allowances would be distributed to farmers based on the size of their landholdings. Farmers who do not burn stubble can sell their allowances in a regulated market, providing an additional income stream.

3. Monitoring and Enforcement: Satellite imagery and ground inspections would monitor compliance. Farmers found burning stubble without allowances would face penalties.

4. Support and Subsidies: The government would provide financial support and subsidies for purchasing equipment like Happy Seeders and bio-decomposers. Additionally, training programs would be conducted to educate farmers on the benefits and usage of these technologies.

Benefits of the Cap-and-Trade System

1. Economic Incentives: The system provides a direct economic benefit for adopting sustainable practices by allowing farmers to sell unused allowances. This can offset the initial costs of purchasing equipment and adopting new methods.

2. Flexibility: The cap-and-trade system offers flexibility, allowing farmers to choose the most cost-effective way to manage stubble. Those who can adopt alternative methods quickly can profit from selling their allowances.

3. Environmental Impact: Reducing stubble burning will significantly lower air pollution levels, improve public health, and reduce agriculture’s environmental footprint.

Addressing Challenges

1. Initial Resistance: Farmers may resist change due to the force of habit and risk aversion. To address this, the government can provide demonstration projects and success stories to showcase the benefits of alternative methods.

2. Cost of Equipment: The high cost of equipment like Happy Seeders can be a barrier. Subsidies and low-interest loans can help farmers afford these technologies.

3. Infrastructure: Developing the necessary infrastructure for alternative stubble management methods, such as collection centers for bio-decomposers, is crucial. Public-private partnerships can play a significant role in building this infrastructure.

Conclusion

Implementing a cap-and-trade system for rice stubble burning in India can provide a market-based solution to a persistent environmental problem. By setting a cap on stubble burning and allowing farmers to trade allowances, the policy would create economic incentives for adopting sustainable practices. Coupled with government support and infrastructure development, this approach can significantly reduce air pollution, improve public health, and promote sustainable agriculture. The success of the U.S. cap-and-trade system for SO2 emissions provides a compelling blueprint for India to tackle its stubble-burning issue. With careful planning and implementation, a similar system can help India achieve its environmental and agricultural goals, ensuring a healthier future for its citizens and the planet.

Image credits: BBC