The Nutrition Cost of Free Trade: Why the India–UK FTA Must Guard Against Ultra- Processed Food Imports

After years of intense negotiations, the India–UK Free Trade Agreement (FTA) is nearing the finish line. Touted as a landmark deal, it promises mutual economic gains: India gains better access to UK markets for textiles, pharmaceuticals, software, and more, while the UK secures a foothold in one of the world’s fastest-growing consumer economies post-Brexit.

Lower tariffs, fewer regulatory hurdles, and seamless cross-border transactions are central to the FTA. Policymakers on both sides hail the agreement as a win-win — a vehicle for growth, innovation, and job creation. But buried beneath these economic headlines lies an overlooked but crucial question: what will this deal mean for public health — and more specifically, for India’s food system?

Trade agreements are not just economic instruments; they have far-reaching implications for what people eat, how food is produced, and who controls the food supply. The India–UK FTA, in its current form, may unintentionally open the floodgates to ultra-processed food (UPF) imports, with potentially disastrous consequences for India’s already fragile nutrition landscape.

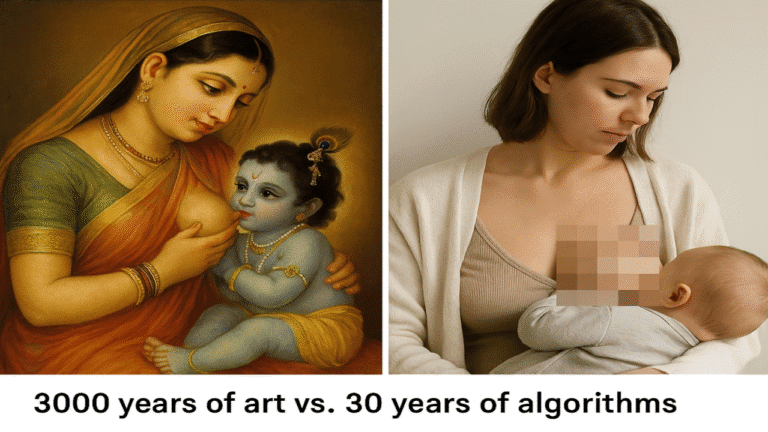

According to the NOVA classification system, ultra-processed foods are industrial formulations primarily made from substances extracted from foods or synthesized in laboratories: preservatives, flavourings, colourings, added sugars, and hydrogenated oils. These are foods engineered for convenience, shelf life, and hyper-palatability — think chips, soft drinks, sugary breakfast cereals, candy, and instant noodles.

The draft India–UK FTA proposes the elimination of tariffs on 99% of products, including animal products, vegetable oils, and processed foods. While this might appear beneficial for consumer choice and market competition, public health experts warn it could flood Indian markets with cheap, aggressively marketed UPFs — products known to contribute to obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and other non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

India is not the first country to face the nutrition fallout of trade liberalisation. The experience of Mexico under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is a cautionary tale. NAFTA, implemented in 1994, dramatically transformed Mexico’s food environment. With tariffs lowered and U.S. investments surging, ultra-processed food and beverage companies like Coca-Cola expanded aggressively. By 2002, Mexicans consumed more Coca-Cola per capita than Americans, and obesity rates soared. Between 1988 and 1999, obesity prevalence jumped from 33% to 59%, and traditional diets based on corn, beans, and squash were rapidly displaced by processed imports. The result? A public health crisis driven by dietary change.

Australia’s trade deal with the U.S. offers another troubling precedent. Post-agreement, imports of sugary drinks and snack foods surged, propelled by relaxed tariffs and aggressive corporate marketing. UPF consumption rose, with measurable increases in obesity and metabolic disease.

India risks walking the same path. British-based food giants such as Nestlé UK, Cadbury- Mondelez, and Unilever UK are major players in the global UPF market. Once tariff barriers fall, these companies are poised to expand their footprint across India, especially in urban markets where demand for convenience and packaged foods is high. Backed by sophisticated marketing, attractive packaging, and low prices, these products are likely to find a strong foothold.

This risk is especially stark given India’s current nutrition profile. The country faces a dual burden: persistent undernutrition coexists with rising obesity and diet-related NCDs. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), the proportion of overweight

children under five increased from 2.1% in 2015–16 to 3.4% in 2019–21. Meanwhile, 6.4% of women and 4.0% of men aged 15–49 are obese — figures that continue to climb.

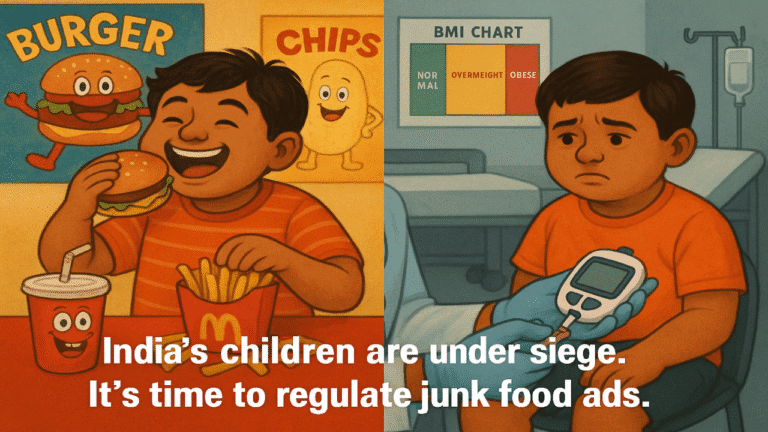

Among urban adolescents, the picture is more alarming. The proliferation of food delivery apps, digital marketing, and the unregulated sale of junk food in school canteens only exacerbate the problem. If the India–UK FTA lowers prices and expands availability of UPFs, it could further erode traditional food habits and exacerbate the nutrition transition — with lasting damage.

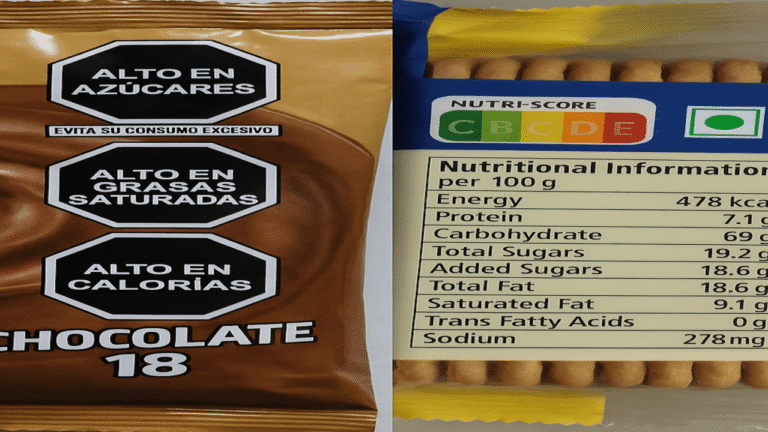

What’s concerning is the disconnect between India’s trade and nutrition policies. Free trade agreements like the proposed FTA often exclude considerations of dietary health. India still lacks a comprehensive policy framework to regulate UPFs — there are no mandatory front-of- pack warning labels, few advertising restrictions (especially for digital media), and no taxes on high-fat, sugar, and salt (HFSS) products.

In this context, prioritising short-term economic gains without accounting for long-term health costs is dangerously short-sighted. India must urgently implement safeguards to protect public health before finalising the FTA. A good starting point would be conducting a comprehensive Health Impact Assessment (HIA) of the agreement — to identify nutritional risks and propose evidence-based mitigation strategies.

Second, sensitive food categories such as sugary drinks, candies, and HFSS snacks should be excluded from tariff reductions. This approach is not unprecedented: countries like Mexico and Chile have taken strong policy steps to shield their populations from UPFs, introducing warning labels, advertising bans, and fiscal measures.

Third, India must strengthen domestic regulations: mandatory front-of-pack warning labels; strict limits on junk food advertising (especially to children); and taxes on sugary and ultra- processed products. These policies would curb demand and deter companies from exploiting gaps in the regulatory system.

FTAs, if wisely negotiated, can promote nutrition rather than undermine it. They can facilitate trade in healthy foods — fruits, millets, pulses, and traditional grains — and channel investments into food infrastructure like cold chains, agro-processing, and sustainable supply

chains. But this requires a fundamental rethinking of trade not merely as an economic tool, but as a lever for public well-being.

India is at a critical juncture. As it negotiates FTAs with global partners, it has an opportunity

— and a responsibility — to champion a new model of “nutritionally sensitive trade.” Aligning trade policy with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on health, nutrition, and well-being isn’t just good governance; it’s essential for building a healthier future.

In the race to globalize markets, we must not globalize malnutrition.